Sale on canvas prints! Use code ABCXYZ at checkout for a special discount!

"Praises to you, O moon, Djehuty,

strong bull of Hermopolis, dwelling in its sacred precinct,

One who clears the way for the gods, knows the religious mysteries,

writes down the statements of the gods;

Who distinguishes one report from another like it

and evaluates each person;

Skilled to guide the Bark of Millions of Years;

Courier for the Sunfolk,

Who knows a man by his speech

And measures the deed against the doer”.

- From the Hymn to Thoth on a statue of Horemheb in New York

Hymns, Prayers, and Songs: An Anthology of Ancient Egyptian Lyric Poetry

Translated by John L. Foster. Scholars Press, 1995, pp. 111.

When I was six years old I had my first powerful brush with the gods of ancient Egypt. In the pages of Encyclopedia Britannica I found photographs of statues, bas-reliefs, amulets, coffins and paintings depicting super-human beings with animal heads…jackals, snakes, cats, crocodiles and a dung beetle. A glittering golden icon of the god Ptah with his characteristic skull cap, a treasure from the tomb of Tutankhamun, enticed me to keep looking, to dig deeper for more. For most people unfamiliar with the nuances of ancient Egyptian art and religious iconography, the goddesses and gods of the Nile Valley present a bewildering and incomprehensible spectacle. A fusion of human and animal, each bearing their own set of complex crowns, regalia and signs, the netjeru or gods embody the fantastical and magical, seemingly defying the mortal realm and anything we could recognize as logical. The gods of ancient Egypt appear to defy logic, and are infinitely locked within the framework of their strange myths.

I was bitten by the bug (or should I say Scarab? ) of ancient Egypt at an age when other kids were discovering cowboys and Indians and J.I. Joe. Today this would be nothing unusual, as ancient Egypt is all the rage from grade school to high school, and the Internet has created an endless place for discovery and research geared towards young people who are fascinated by this ancient world of pyramids and mummies. “King Tut” is a household name even for kindergarteners, and the recent global exhibitions of the Tutankhamun treasures (among many other collections currently circulating) have perpetuated the continued legacy of Egyptomania like never before. However, I grew up in the era before personal computers, the Internet and the iphone (I’m kidding, right?). I grew up before Border’s and Barnes & Noble, before you could walk into any bookstore and find countless books on ancient Egypt to satisfy the voracious appetite of any Egyptophile. I had to make due with the few and far between titles available in mall bookstores or school libraries. When I did find those rare books (like E.A. Wallis Budge’s The Egyptian Book of the Dead or Mildred Mastin Pace’s Wrapped for Eternity ), I devoured them greedily, taking notes and poring over the pictures for countless hours on end. Yes, it was the mummies and monuments, the fabled riches of Tutankhamun’s tomb that drew me in, but even more than those was the religion and magic of a world with which I increasingly found myself identifying. More than anything else from that culture, it was the gods of ancient Egypt that spoke to my mind and seemed to tug incessantly on the strings of my heart.

My first personal experience with an Egyptian deity happened some time after my seventh birthday. I was hospitalized for a severe concussion after falling over a tricycle, and I remember a terrifying moment when nurses were attempting to draw blood, and I squirmed around trying to prevent them from doing their job. I remember my stomach heaving, vomiting, an intense fear coupled with the fierce desire to get out of that hospital. It was then that I prayed to Imhotep- that most famous of Egyptian architects and physicians who after his death was deified as the son of the god Ptah and worshiped as a miraculous healer. I called on him and asked him to make it all better, and that’s exactly what happened. Call it a fantasy or a concussion-induced hallucination if you must, but I will never forget the vision I saw above my hospital bed: A shaven-headed and wise-looking man with a scroll of papyrus unrolled on his lap, surrounded by a scintillating golden aura. He spoke words in a language I did not know in my intellect, and yet my heart seemed to resonate with the sound and meter. All at once I felt a peace and comfort settle over me, and from that day to this I have called upon Lord Imhotep whenever in pain or in need of healing.

“Great One, Son of Ptah, the creative god, made by Thenen,

begotten by him and beloved of him, the god of divine forms in the temples,

who giveth life to all men, the mighty one of wonders,

the maker of times, who cometh unto him that calleth upon him,

wheresoever he may be, who giveth sons to the childless,

the chief Kheri-heb, the image and likeness of Thoth the wise.”

- Address to Imhotep in the temple of Imhotep at Philae

Imhotep by Jamieson B. Murry, M.A., M.D. Oxford University Press, 1926, pp. 46.

While in grade school I attended St. Alban’s Perish Day School, a private Catholic school, where every Friday we were required to attend chapel, take part in Mass, and to observe the saying of the Lord’s Prayer together with those prayers reserved for the feast days of various saints. I had been raised in the Baptist Church, which for me was appallingly sterile and devoid of mystery or passion. It was my experience with the solemnity and ritual of Catholicism that was to change the way I viewed religion. In the Baptist Church of my upbringing there was little to endear a heart already absorbed in the study of ancient rites of a pagan culture; enduring hour-long sermons in stiff pews surrounded by stark white walls and a plain wooden altar. This is as agonizingly boring as religion gets! However, Catholicism struck a chord with me, and in it I identified with something that seemed to originate in a time and place much older than the origins of Roman Catholicism. When attending Mass- hearing the chants in Latin, being imbued with incense clouding up from swinging censors, seeing gilded icons glowing mysteriously by candle light- I connected with the temple rituals of the ancient Egyptians, for something in my heart recognized the sound of chanting, the smell of incense, and the power of golden icons.

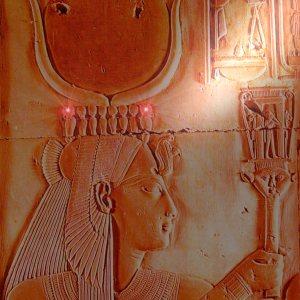

In chapel there was an especially beautiful marble statue of the Virgin Mary, before which always burned dozens of votive candles in blue glass holders. I remember the morning I made my first prayer to Mother Aset (Isis), seeing in the smiling face and outstretched arms of Christ’s mother the spirit of a much older goddess, whose son Heru (Horus) was the savior-god of the ancient Egyptians. At this time I did not yet have my own statues of the Goddess to adore, so I used the statue of the Virgin Mary as my “stand in” to reach Isis. How can I forget the day Father Treat found me lighting a candle in front of the Virgin and said with a smile, “You are praying to Our Lady?” “No”, I answered with an even bigger smile, “I am praying to Isis”.

“Praise to you, Isis, the Great-One,

God’s Mother, Lady of Heaven, queen of the gods.

You are the First Royal Spouse of Omnophris,

The supreme overseer of the Golden-Ones in

The temples, the eldest son, first(born) of Geb.

Praise to you, Isis, the Great-One,

God’s Mother, Lady of Heaven, queen of the gods.

You are the First Royal Spouse of Omnophris,

The Bull, the Lion who overthrows all his enemies,

The Lord and ruler of Eternity.”

- Hymn to the goddess Isis from the temple of Isis at Philae

Six Hymns to Isis in the Sanctuary of Her Temple at Philae and Their Theological Significance. Part

I . By L. V. Žabkar. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 69 (1983), pp. 115-137

Isis was the first goddess of the Egyptian religion to answer my prayers. I came to her at first very timidly, not quite sure how to address a goddess, as I had been raised in the Baptist Church of Christianity, which recognized no goddesses and had no concept of the divine feminine. But I was enchanted by her story, because Isis is no ordinary goddess. Queen of Heaven, yes. Great of Magic, but of course. Crowned and arrayed in the trappings of royalty, to be sure. However, Isis is no loller on the clouds of divine queenship. She is a goddess who knows the sufferings of widowhood, homelessness, imprisonment, forced manual labor, single parenthood, poverty…and the list goes on and on. Something that won the hearts of millions of the ancients was the truly humble story of this powerful goddess whose husband (Asar or Osiris) was brutally murdered, who then had to flee for her life as a widowed and pregnant mother, to give birth in the marshes of Egypt in hiding and on the run from her husband’s murderer. Isis raised her son Horus in secret, ever aware that the chaotic Set (the murderer of Osiris) would destroy not only her but also her young son. The trials of single motherhood in this day and age included near death encounters with scorpions and crocodiles, and the added humility of begging for scraps and help from rich matrons who slammed their doors in the goddess’ face.

This was the story that captivated the ancients, and, when Christianity was struggling to overtake the East, made it difficult for evangelists to convert adherents of the Goddess to the doctrine of Christ. The faith of Isis, Osiris and Horus is the story of a divine family enduring and transforming through very human circumstances. It is also the story of resurrection from death that formed the foundation of the Egyptian belief in immortality and physical resurrection from the dead. Long before Christians formed their doctrine of a divine son crucified and resurrected from the dead as the path to salvation, the very ancient Egyptian religion asserted the death and resurrection of its god Asar (Osiris), and the guarantee of his story to all Egyptians that they could follow in his footsteps and be risen from the dead into the paradise of the Blessed. Central to this belief was the magic of the goddess Isis, who had used the insurmountable skill of her magic to revive her murdered husband from the dead. Upon achieving her aim, she conceived a holy child, the falcon-headed god Heru (Horus), who became to the Egyptians the very embodiment of divine justice, truth, and righteousness.

The story of Heru’s struggle to overcome the obstacles of his tumultuous childhood and regain the throne of Egypt from the murderer of his father had a particular meaning to me as a young boy; for the story of Horus is essentially the story of history’s first underdog turned top dog. He is a child who experiences severe tragedy and darkness, then, as a young man, enters a vicious struggle against his uncle in order to regain his stolen throne. The trials of Heru seem to know no bounds, but he is, in the end, rewarded with justice, and himself becomes the embodiment of truth overcoming brute force and immorality. Horus, once perceived as the outcast renegade of the Egyptian marshes, proves his valor to the gods of Egypt, and wins the kingship of his father as the god of strength and honor. To a young boy who was also a runt, often an outcast amongst other children his age and the butt of many a joke, the story of Heru made me believe in the probability of noble character to surpass mere brute strength, and the significance of maintaining one’s moral and spiritual integrity even in the face of the most violent opposition. My prayers to Isis and Osiris inevitably included earnest petitions to the holy son Horus, the valiant god whose power of truth could help me defeat the schoolyard bullies, and survive the heartache of a troubled domestic life.

“I am Horus the Behdetite, great god, lord of the sky,

Lord of the Upper Egyptian crown,

Prince of the Lower Egyptian crown,

King of the Kings of Upper Egypt,

King of the Kings of Lower Egypt,

Beneficent Prince, the Prince of princes.

I receive the crook and the whip,

For I am the lord of this land.

I take possession of the Two Lands

In assuming the Double Diadem.

I overthrow the foe of my father Osiris

As King of Upper and Lower Egypt for ever!”

- The speech of the god Horus from his temple at Edfu

The Triumph of Horus: An Ancient Egyptian Sacred Drama. Translated and edited

By H.W. Fairman. University of California Press, 1974, pp. 106.

I was raised in a very religious family, and I have always been a very religious person. I was even religious as a kindergartener. My problem as a child was that I was drawn to the “wrong” religion. Something about monotheism stuck in my craw and seemed to chew up my insides. And something about church made me shake me head for want of something more. Where are the statues?, I remember asking myself while daydreaming during Sunday school about being anywhere but there. Where are the flowers, the chants…the Mysteries? They had these in ancient Egypt, I told myself, so why shouldn’t they be in the houses of God now? Somehow, it all seemed wrong to me, and I never felt very right sitting in those stiff wooden pews surrounded by black-tied and suited fathers beside their starchy looking wives. I couldn’t stand church, because to my little mind it felt completely separate from the Divine. It seemed more about who was wearing what, and showing off good Christian morale than about finding and serving God. And which God?, I always asked myself. Some distant and wrathful old man flying around out there, just waiting to send irredeemable souls to the lake of fire. Even at eight-years-old I said to myself that one god was just not enough, let alone a jealous and angry god that would condemn his “chosen people” to forty years of hard time in the wilderness. So, I opted for something else.

When I was entering puberty my father told me I needed to be baptized. He was close friends with the preacher, whose son was just about my age and was going to be baptized in a group ceremony for young adults. And how would it look if I decided not to be baptized too? How would it make my father look, my family? Church was, after all, a place where one’s status in society could be firmly established. It’s where you showed off your new car, your wife’s 24 karat gold rope chain, your son’s straight A report card. It was also about showing off your Christian do-goodness. My parents were ahead of the game in that department. They volunteered for everything they could, everything from Wednesday night youth group to Sunday picnics and fund raising bake sales. My father was a pillar of the church, so his son just had to be baptized with the other boys. Period. So I went to baptism class with the preacher’s son, memorized bible verses and evangelical prattle, and generally hated myself because I didn’t believe in any of it, and felt impure at the thought of taking part in it. Why did I feel impure? It wasn’t because I felt I was tarnishing Christian values by taking part in something so sacred without being a believer. That thought never crossed my mind. I felt overwhelmed by a sense of slandering the gods I truly believed in, the gods I kept locked away in my heart so that my Christian parents couldn’t see them. I would betray anyone, anything but them. How could I go through with it?

I stood behind the baptismal tank with all the other boys, dressed in my pure white robe, looking up behind the altar at a blue-painted sky in which clouds beckoned the mind to dwell in Christ’s kingdom. But my mind was lower than low, consumed in guilt and conflict, because I was consecrating my body (and, supposedly my soul, too) to the Christian faith in front of the whole community. But then something happened. I felt a presence leading and guiding my heart into awareness of how this moment could be transformed into something sacred for my personal religion, for my gods and my true beliefs. Looking at the four corners of the baptismal tank, I saw in my mind’s eye the four tutelary goddesses of ancient Egypt: Aset (Isis), Nebet-het (Nephthys), Selket and Neith. Their kind expressions and outstretched arms surrounded the waters in a protective embrace, just as they had the fabulous golden canopic shrine of Tutankhamun. And I saw the baptismal tank not as the waters in which John the Baptist had Baptised Christ, but rather as the waters of the sacred Nile, the holiest of rivers to the ancient Egyptians. And I called on the gods of those people, just as I was summoned to take my turn in the waters. I offered to them the vessel of my heart in sacrifice, and gave over my soul, my mind, the entirety of my being, to them and only them. With my mouth I parroted the words the minister spoke, the words he and everyone else believed would make me a true and consecrated Christian- but in my heart I prayed fervently to my gods, and gave myself over into their sacred care. When I was dipped beneath the waters I experienced them as the same waters in which the god Osiris was drowned, the waters beneath which opened up the hidden passage to the Netherworld. And I entered, and from that moment on I belonged to the living gods of ancient Egypt. Like Osiris, I died and was born again, and my life was the vehicle for the glorious gods who still spoke and moved when they were listened to and called upon.

“I come unto thee, son of Nut, Osiris, ruler of eternity. I am a follower of Thoth, rejoicing in all that he has done. He brings for thee refreshing breath to thy nose, life and dominion to thy beautiful face, and the north wind that came forth from Atum to thy nostrils, lord of the sacred land. He lets the light shine on thy breast; he illumines for thee the way of darkness”.

- Excerpt from Spell 183 of the Book of the Dead

The Book of the Dead or Going Forth By Day: Ideas of the Ancient Egyptians

Concerning the Hereafter as Expressed in their Own Terms. Translated by

Thomas George Allen. The University of Chicago Press, 1974, pp. 200.

My Kemetic (ancient Egyptian) icons are my answer and my call to the gods of the Nile Valley. However, these gods are not just fixed in space and time, belonging only to the hazy mythos of a long-dead civilization, nor are they solely the gods of ancient Egypt as a historical culture or geographical location. The netjeru or gods are manifestations of the Eternal, beings who both embody and transcend the extraordinary culture that first recognized them as the components of all life. Nor can they be boiled down to mere archetypes, the play of the human intellect as it attempts to define the undefinable and bestow meaning to what is beyond comprehension. I must ask how an archetype is worthy of worship? Do Christians, for example, worship Christ as an archetype of resurrection or salvation? Do they view his power solely as that of some abstract symbol by which the human mind can label a thing hidden deeply within the recesses of its own mind? The answer is self-evident. The passion of Christianity lies in the physical existence of Christ, in his historical passion of birth, death and resurrection, in the redemption literally passed down to humankind through the spilling of his blood. There is no Jungian symbolism or Freudian theory that can define for Christians the solid truth of Christ’s sacrifice and promise. So too did the ancient Egyptians view their gods as historical and tangible beings, incarnate in and through the created world. Their powers were very immediate, very real to the mind of the Egyptian, who did not bother with abstract universal thinking, but opted instead to experience the Divine in the here and now, in the flesh, and in the world beyond this one that was as earthy and tangible to the Egyptians as their beloved Egypt.

There are those who, in the spirit of New Age thought, assign the gods to the Jungian realm of abstract symbols inherent to emotional states of being, or simply define them as “nature”. The true gods laugh at such egoistic folly, as human beings strive to quantify, label, and explain away through tidy language the quintessence of the Mysteries. My experience of the gods is that just when you find a convenient label to slap on them, they are sure to change and transcend logic in all its secure forms. That is why the netjeru were served by the ancient Egyptians through the cultic rites they called shetau, “the mysteries”, from a word meaning to “make secret”, “make inaccessible”, “mysterious”, “confidential” (Raymond O. Faulkner, A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, pp. 248-249). The gods so enjoy the delicious complexity of form and symbol, name, color, texture and transformation. To the ancient Egyptians, each deity was the composite of nearly limitless qualities and manifestations of form. Each assisted in lending the power of recognition to the whole; however, ultimately the gods were mysterious and hidden, experienced truly through the magic of ritual and iconographic forms.

So, I wish not only to connect with the netjeru personally as a devotee summoning up their images within the artistic medium, but also to bring these gods to humankind once more. The mission of my creativity is to literally give birth to the gods, for we are told in the so-called Memphite Theology of the Shabaka Stone that the creator-god Ptah determined the offerings and places of worship of the gods, that he made their body as they desired, and that because of this the gods entered into their bodies of all kinds of wood, minerals, clay, and all kinds of other things that grow thereon (Holmberg, The God Ptah, pp. 22 ). It is through the artistic medium, then, that the gods make contact with human beings, for the artistic medium is that process by which wood, stone, minerals, clay, and the substances that have sprung from the earth are transfigured into the shapes in which it pleases the gods to dwell.